By Victoria Jackson, Daniel Murchison, and Carolyn Podruchny*

We thought there were only two ways on and off Manitoulin Island: driving over the Little Current Swing Bridge along Highway 6 on the north shore, or arriving at South Baymouth on the south shore via the MS Chi-Cheemaun ferry from Tobermory on the tip of the Bruce Peninsula. We were wrong. The “Manitoulin Island Summer Historical Institute (MISHI) 2017: Does Wisdom Sit in Places? Sites as Sources of Knowledge,” a five-day summer institute held from August 14-18, 2017, taught us that the wisdom and knowledge on Manitoulin Island travels over many bridges.

MISHI 2017 focused on understanding how place-based knowledge shapes an Anishinaabe-centred history of Manitoulin Island and its environs. Co-sponsored by the History of Indigenous Peoples (HIP) Network, a research cluster embedded within the Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies at York University, and the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation (OCF), an organization devoted to Anishinaabe history and culture, the summer institute brought together 25 established and emerging historians, graduate students, administrators, artists, Elders, and knowledge-keepers to explore the history through landscapes, stories, and documents. The OCF represents six First Nations (Aundek Omni Kaning, M’Chigeeng, Sheguiandah, Sheshegwaning, Whitefish River, and Zhiibaahaasing) and is dedicated to nourishing and preserving Anishinaabe history, arts, language, and spirituality. MISHI seeks to break down historically, socially, and spatially made boundaries between knowledge systems, people, and communities for the purposes of engagement with Manitoulin’s Anishinaabeg-centered history and culture. MISHI 2017 ended up being a lesson in building bridges.

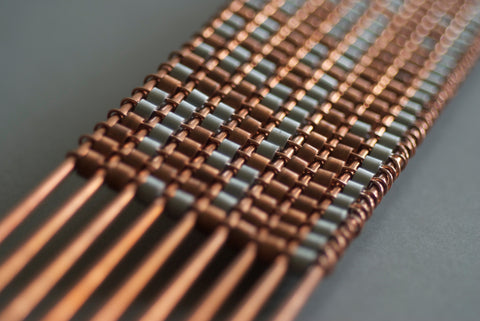

Image 1: Michael Belmore, “Bridge,” 2014

To inspire us to focus on finding connections, the signature image of MISHI 2017 is Anishinaabe artist Michael Belmore’s Bridge, a wampum belt modelled on ancient material treaties that were typically made from quahog shells, and, as Belmore reminds us, historically distributed to establish and reinforce social and political agreements between and within Indigenous nations. The piece Bridge, however, is made of cooper and aluminum beads arranged to represent the 1’s and 0’s of ASCII binary coding typically used in the operations of computers, cell phones, and video game consoles. According to Belmore, the braiding of traditional format with an often obscured digital language highlights “the forgotten codes that are the basis of contemporary realities that serve to connect, and sometimes divide, our communities.” The piece allows viewers to contemplate the supposed dichotomies between past and present, traditional and modern, analog and digital, and Indigenous and non-Indigenous technologies. Reading this piece requires active engagement, and like traditional wampum, insists on a responsibility in that interaction. Through its disruption of supposedly mutually exclusive knowledges and technologies, the Bridge piece is an instructive mechanism for thinking about the links this summer’s community-engaged field school drew across disciplines, across knowledge systems, across institutions, and across generations.

In the evening of Sunday, August 13th, the various participants arrived on the Island via ferry or swing bridge, and met at the Providence Bay Tent and Trailer Park for a welcoming dinner. The requisite round of introductions, covering both scholarly interests and institutional affiliation, revealed historians, environmental studies scholars, political scientists, film-makers, literary scholars, and anthropologists. While most travelled from southern Ontario, others came from British Columbia, Arizona, Peru, and India. Elder Lewis Debassige of M’Chigeeng First Nation (and co-organizer for MISHI) explained that “Manitoulin” means “Spirit Island” and shared his extensive knowledge of the Island’s long history, drawing attention to its distinct place within the lifeworlds of Anishinaabe people. Contemplative dinner conversations forged areas of mutual interest and Lewis’s mingling and sharing of his stories created the context to forefront reciprocity between people and land, which was the first of MISHI’s bridges.

Figure 2: Interior of Ojibwe Cultural Foundation

On the morning of Monday, August 14th, we gathered at the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation (OCF) to work as volunteers. Exchange of labour and knowledge is at the heart of MISHI, to build a bridge across Anishinaabe and academic institutions. Lewis Debassige opened MISHI with a prayer. Elder Peggy Pitawanakwa and her granddaughter Natalia (Wikwemikong First Nation) smudged everyone to ensure we started the field school in a good way. Anong Beam (M’Chigeeng First Nation), Art Director of the OCF, gave a brief history of the organization and its mandates before we began our assignments for the OCF. Participants are producing booklets on various topics of Manitoulin-centred history for use in local schools and for sale to the general public (with profits going to OCF). In addition, participants are building on OCF’s archival and oral history collections by recording and transcribing interviews with Lewis and the MISHI presentations.

Our afternoon was devoted to a four-hour tour of the central part of the Island to learn first-hand about the wisdom sitting in the Island’s places, led by Lewis and former OCF director Alan Corbiere (M’Chigeeng First Nation). The stories we heard featured the Trickster Nanabush as a central figure in the creation of the world and its features. In one example, Alan shared a story of the formation of Mindemoya (Old Lady Island) involving Nanabush and his grandmother repelling a threat by the Haudenosaunee. In another, Nanabush fell, leaving an imprint of his bum in the earth. Each of the stories connected people to land and taught us how to read Anishinaabe history through places, as the geography of place inscribes its history. Lewis and Alan taught us to navigate their bridge between Anishinaabe ways of understanding the past and the academic requirements of the discipline of history. These themes were evident in Michael Belmore’s art installation, Replenishment, a tryptic of three carved boulders designed to speak to one another placed in the Kagawong River to draw attention to Anishinaabe people (represented by the water) washing away the social and environmental effects of colonialism.

Image 3: Michael Belmore,“Replenishment,” 2015 in the Kagawong River (courtesy of Nicole Latulippe)

On our second day, we visited Whitefish River First Nation and the sacred site of Dreamer’s Rock, located just north of Manitoulin on Birch Island. In accordance with the community’s wishes, no recordings were made or photographs taken. We listened to the oral histories of the site told by Deborah McGregor (professor in Law and Environmental Studies at York University, and member of Whitefish River First Nation) and her mother Marion McGregor, before hiking up to Dreamer’s Rock, where we encountered a metaphysical bridge to the spiritual world. Continuing our discovery of incorporeal bridges, in the evening we attended an OCF storytelling session with Elder Willie Trudeau on the Seven Prophecies of Anishinaabe history. As with Alan Corbiere’s stories of Manitoulin Island’s history and its peoples, Elder Willie’s history was rooted firmly in places. He told us an expanded version of Anishinaabeg migrations, highlighting Turtle Island’s stopping places along the migration routes. He also told us about the trauma of residential schools, and how the loss of language and culture had spirituality affected him and other survivors and their families. We learned that the work that he and other knowledge-keepers were doing is helping everyone heal and re-establish their relationship with the land. In many ways, his stories and testimony underscored the importance of building bridges between communities, institutions, and individuals, so that the survivors of colonialism’s atrocities could heal.

Image 4: Josh Manitowabi (MISHI participant) and Alan Corbiere discussing wampum belts

(courtesy of Clara Fraser)

The bridges we learned about on our third day involved treaties, families, and spirituality. We began at Manitowaning, at the site of the signing of the 1836 and 1864 Manitoulin treaties, where Alan Corbiere discussed the role of wampum in relations between Anishinaabeg and the British government, displaying his beautiful wampum belt reproductions. His combination of written sources, oral histories, wampum belts, and place united divergent historical traditions, and helped reinforce not only the validity of different ways of knowing but also emphasized that a singular vision or way of knowing (a sole bridge) obscures our understanding of the past. Our next stop was the large unceded reserve of Wikwemikong (Wiky), where Elder and knowledge-carrier Steve George (Wikemikong First Nation) shared his family history and an album of photographs to highlight personal connections with these histories. Steve took us to see the ruins of a residential school where the De-ba-jeh-mu-jig Theatre Group had installed a healing lodge as part of their open-air performances. Here Peggy and her granddaughter Natalia welcomed us to Wiky with a give-away ceremony of sweet grass, a sacred plant that encourages positive connections and helps build bridges.

Image 4: Natalia Pitawanakwa and Katherine MacDonald preparing sweet grass for give-away ceremony

(courtesy of VK Preston)

The talks of the last days offered participants an opportunity to think about local histories through various settings and materials. Presentations by Anong Beam and archaeology professor William Fox (Trent University) drew our attention to the ways in which the pursuit and production of historical knowledge is partially rooted in personal understanding and experience. First, Anong talked about her childhood travelling around North America with her father, artist Carl Beam, to uncover Anishinaabe ceramic techniques, as well as her contemporary pursuit in placing those traditions in the present through teaching sessions and the repatriation of pottery taken after a dig in the 1980s. Then William illuminated the ancient history of southern Ontario, including the multi-layer transportation and trade networks created by Great Lakes Anishinaabeg. He led our group to the site of an ancient village on the outskirts of Providence Bay, whose existence stands as proof of a deep, lasting, and personal history on the Island. Indeed, the ancient site was the strongest bridge to an ancient past.

Our education in material culture continued at the OCF that afternoon with a bannock-making workshop, led by knowledge-carrier and M’Chigeeng First Nation member Patsy Panamick. Here we participated in a form of household labour, and, from the boisterous conversations around the working tables, its social underpinnings. The bannock made by members of the field school contributed to the evening’s community feast which was then followed by Anishinaabe artist Nico William’s first solo showing, titled “Spirit Transformation.” Consisting of fifteen intricate sculptures in the form of hyperbolic pyramids, his pieces braided together Anishinaabe sacred stories and his own family histories of pain and resilience, infusing practices of traditional quillwork and beading with new meanings. The next morning Nico taught us to bead rings in honour of the first Pride Weekend on Manitoulin, which became symbols of commemorating our week of respectful learning.

Image 5: Nico Williams, “Spirit Transformation” exhibit at the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation

(courtesy of VK Preston)

Our final presentation was fittingly by sculptor Michael Belmore, whose work is dedicated to North America’s landscapes and watersheds, particularly through the creation of maps hand-pounded into indigenous copper. He explains that “through the arduous process of hammering copper, I have continued to map out waterways through calculated and miscalculated blows…. shorelines … offer the perfect opportunity to demonstrate fully our long influencing actions on landscape. Although this work is not literally in skin, as landscape and as place it is just as much a part of us.” Michael’s work taught us that building bridges is an exercise in persistent, careful, deliberate construction.

The field school ended with everyone checking out of their respective accommodations, getting in cars, having lunch, and, for the most part, boarding the Chi-Cheemaun ferry for a brief trip back to the mainland. Whether it be in a busy restaurant or the ferry’s viewing deck, these spaces offered participants further opportunities to continue conversations and reflect on a week of engagement with local knowledge. Some will turn into long-lasting relationships and, the continued reflection and planning among participants highlights the institutions’ goal of treating the field school not as a mere event but, rather, as part and parcel of a larger process in drawing academic and Anishinaabeg communities and knowledge together. Tangible aspects, like continued work on the OCF’s educational materials and the transcription of archival content, combine with the intangible, like conversations and friendships, strive to tear down the walls between academic and Anishinaabe history, built by centuries of colonialism. MISHI, like Belmore’s Bridge, offered a distinct opportunity to critically reflect on how we think and act upon relations between people, land, and community. We will continue building.

Constructing and maintaining bridges is comprised of relationships and good will. The co-authors thank MISHI’s organizers -- Anong Beam, Alan Corbiere, Lewis Debassige, Carolyn Podruchny, and Boyd Cothran -- as well as all the speakers, staff, and volunteers, for bringing this year’s Institute together. A big thank you also to the OCF, Abby’s, Ed’s Family Restaurant, M’Chigeeng Wellness Centre, and Lake Huron Fish and Chips for feeding us all at MISHI. None of this would have been possible without the accommodation and patience of all of the people involved – chi miigwech!

Image 6: Participants of MISHI 2017

* Victoria Jackson, MISHI 2017 participant, is a senior doctoral candidate in the Graduate History Program at York University, working on 17th-century Wendat children’s history. Daniel Murchison, MISHI 2017 participant, is a junior doctoral candidate in the Graduate History Program at York University, working on Anishinaabe history. Carolyn Podruchny, MISHI 2017 co-organizer, is an Associate Professor in the History Department at York University.